Racist. Racism. Race.

These are words that bring to mind different reactions depending on one’s color, origin, and experience. The names people use to describe themselves in this context may evolve over time, from white supremacist to white nationalist to patriot, but the scars these ideologies inflict on society are the same today as they always have been. Most who participate in this type of behavior and name-calling are not always aware of the implications of their actions. That is the reality, even in 2017.

There has been much discussion over the past year, from the U.S. Election cycle and its newly minted administration to the unfettered racial violence throughout this country and many others. It has brought to the surface my personal scars that were painfully earned, as I left one country for another.

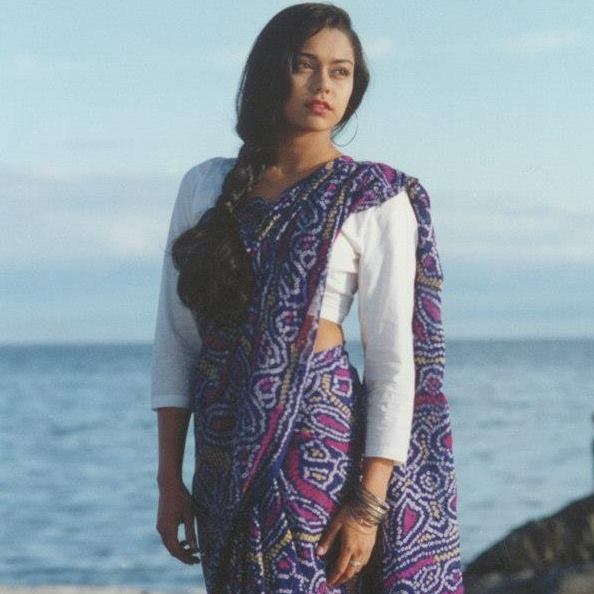

I was born in the state of Odisha in India. My first five years were spent surrounded by family, from my grandmother and cousins, to aunts and uncles, and assorted other relatives. It was easy. I was loved. And I didn’t comprehend the connection at the time, but I looked like everyone else.

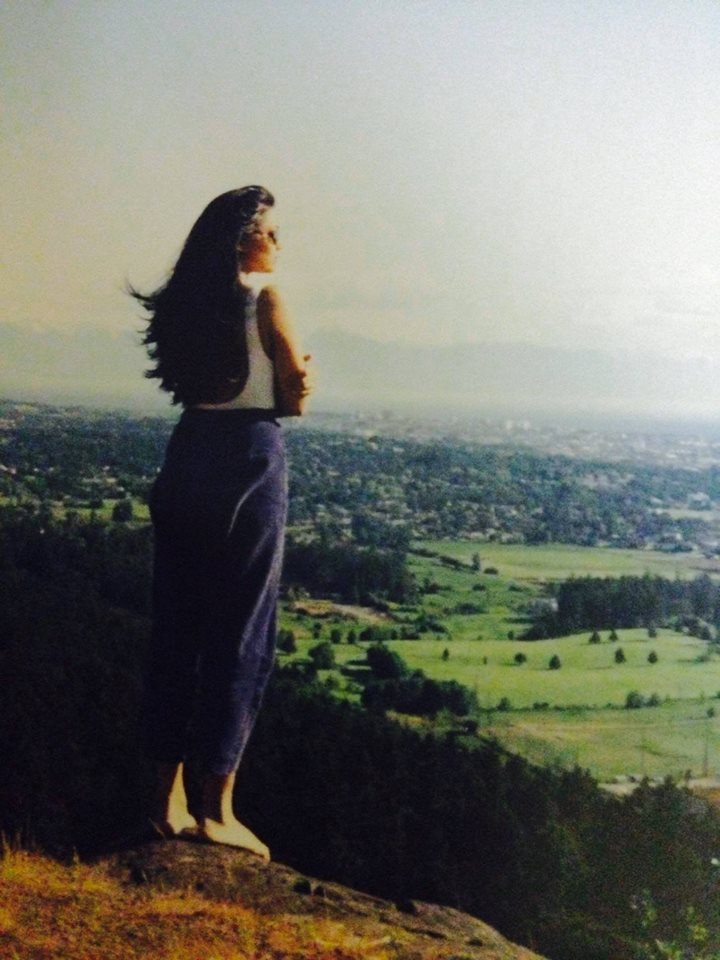

I traveled to Canada in late August, a few months shy of my sixth birthday to join my father and mother, who were already math professors at the University of Victoria. I remember how cold and grey and misty it was the day I arrived, and how scared I was that my grandmother was not next to me. I didn’t understand a single word. I spoke only Oria. English was a harsh and foreign sound to my ears.

It was hard to look around and not see one person that looked like me. Not one person who sounded like me. The sights were strange, the smells were unusual, and the tastes would take some getting used to.

What I remember distinctly that first year at school is two things. Firstly, I got wonderful hugs from my teacher, Mrs. MacArthur. She smelled like mints and flowers. I liked those smells immediately. Even today, when I smell mint, I’m reminded of that petite blond haired lady in a pink polyester pantsuit, ready to greet me with a smile and an embrace. The other thing I remember clearly, is being cornered at lunch by three classmates, two girls and a boy. They each had blond hair and light eyes, and peered at me suspiciously just outside the girls’ bathroom.

I had learned enough English by then to understand their concerns. They had several questions. They wanted to know if I bathed. And if so, why was my skin so much darker than theirs? Was I unclean? Was hygiene the issue? Unfortunately I didn’t know enough English to formulate an answer, so my response was a shrug. I thought it would be my salvation, a gesture of solidarity, as I’d seen them do on so many occasions.

But it was not. Those two girls pushed me into the bathroom and into a corner until I fell, sneering at me and calling me names. I was too surprised by this reaction to cry, but I was very, very afraid. Even now, I can taste that fear. Eventually they left, and even though I didn’t fully comprehend what had just happened, it was clear to me that I was different, and for that reason, I was being punished. Confused and hurt, I didn’t speak much that year, in class, nor at home. And I didn’t shrug for nearly a decade.

It was my first experience with those words even though I had no knowledge of those words. It was my first scar. I say it was the first, because it was far from the last. For the next 10 years, school after school, I was made fun of, heckled, threatened, degraded, humiliated, beaten up, shut into lockers, tripped in the hallways, had my hair pulled and called names. Those names… when I hear those same names today, I shudder. A few times I was punched and kicked for no apparent reason, as my school colleagues watched from the sidelines. I resigned myself to the fact that this was my lot in life. After all, I was the interloper, the foreigner, the one that didn’t belong.

In seventh grade, at the age of 11, I had befriended a girl who had moved three houses away from me. She happened to be half Indian. Her mother was from Darjeeling, and her father was from England. But I remember that same girl who refused to acknowledge her heritage by the age of 12, and she wouldn’t even accept that she had black hair. She called it brown. It was bizarre to me. But she was my friend and I didn’t question her, I simply accepted it. When junior high arrived, she told me she could no longer be my friend because “I didn’t fit in.” I remember crying quietly in my room for weeks, but she was gone. I would see her in the hallways, but we didn’t speak for years. How could I blame her? Perhaps that was her way of coping with some of the things I dealt with, her way of separating.

I, on the other hand, couldn’t escape the cards I’d been dealt.

Outside of school grounds, I watched as that ugly word was directed at my mother in traffic, my father at the grocery store, my brother on the street, and towards others who were simply near us and who suffered the same fate. More scars formed, but I was prepared for the pattern of behavior because it was anticipated. On a “good” day, the 14-year-old me would write in her diary: Nobody hurt me, or pushed me down, or said anything mean to me today. In fact, nobody said a word to me all day. It was a good day.

Those who haven’t experienced this particular kind of torment are not able to fathom the damage that can be inflicted, nor the damage I then did to myself. I believed I wasn’t good enough, or smart enough, or white enough. My young brain was not developed adequately to understand the motivation behind the words and the fists.

I have to admit, I was also known as a dork. I was academically gifted. Somehow despite the daily torture, I maintained good grades, I was an obedient girl, and I was pretty quiet most of the time. I can’t say what percentage of that taunting was related to “dorkism” and what percentage was because of the color of my skin. I also didn’t wear trendy clothes, had two long thick black braids, and these three things set me apart from other more normal looking girls. But I was still human, still just a little girl, still deserved basic decency, of this I was sure.

Slowly I began to cling to other words, words with deep meaning. I learned that information is power, that language is key. So, I became a voracious reader. From Somerset Maugham’s short stories to Jude Deveraux’s historical romances, from biographies about Martin Luther King and Mohandas K. Gandhi to the Miriam Webster Dictionary, I read everything I could get my hands on. There was no Internet or Google, just the library, and it became my best friend.

As I changed and morphed into a culturally blended person, Canada began to change as well. I remember the sound of sitar music on Canadian television for the first time. I came rushing out of my room at the age of 15, brush in hand, mouth ajar, as I saw the Bell phone commercial, the announcer talking about discounted calls to India. I remember Monica Deol, the beautiful VJ on the Much Music channel, an Indian woman whom so many revered and praised. I remember the first time my mother bought a bag of basmati rice at Safeway and not at the local Indian store. Small changes, and yet they were so crucial to my formative years. A country that I had believed didn’t accept me, suddenly made me feel warm and fuzzy.

By 12th grade, I spoke three languages. I was also a writer. And I won academic awards. This made my parents very happy. But what it gave me was a greater sense of purpose. Although I was expected to join the family profession, gaining a PhD and go into teaching, I knew, even then, that I was destined for something else. What that was would not be clear to me for many more years.

Although I often felt alone, there were people in my life. I had friends. Good friends. I also had boyfriends, some worse than others. One particular relationship was very damaging. Perhaps he could sense my vulnerability and uncertainty about who I was in this world or maybe he was so self-focused it didn’t matter to him. This person I had hoped would be there for me turned out to be my biggest abuser, a man I foolishly stayed with for ten years. He took every opportunity to remind me of my lack of confidence, and origins. If I commented that I didn’t appreciate what he was implying, he would dismiss it as being too sensitive. He wanted me to feel shame and insecurity because as long as I felt badly about the person I was, he could ignore his own deficits. Character flaws such as excessive drinking. It took me years to acknowledge that he had a drinking problem. Disagreements and fights were always my fault, and I was repeatedly reminded of my lesser position. I know now, this behavior is called gas lighting and is often employed by sociopaths.

Of course, I thought it was my fault because everyone always said, “he’s such a good guy.” And he was. To everyone else. Unfortunately, his abuse wasn’t limited to words and when his belittling was not enough, he became physically abusive. One time he rolled up a Road & Track magazine in his hands, and swatted me on the face with it. Hard. Another time he pushed me so hard, I flew across the room. The last time, he choked me as he repeated threats that he would kill me. Oddly enough, this experience was my turning point. Something awoke inside of me and I began to see myself for the first time. I began to realize how foul his treatment was, and how my devaluation as a child had led me to allow this man to diminish me further as a woman.

The damage that had been done through those early years was neither easy to forgive, nor to forget. But I did know one thing. I knew I wanted to go far, far away from my hometown. I wanted to go to New York, where I had heard stories of the melting pot. I was excited about a country that I thought had already fought their battles with that word, where I believed a deeper understanding existed between cultures. I believed nobody was a foreigner because everybody was a foreigner.

Those words that had started this independent search for truth and justice could not end without a purpose. After all, everything happens for a reason, right? And so, I set my sights on the Big Apple. Everybody told me it was impossible, not only because of the opacity of immigration laws, but also because there was no family, nor friends close by. Turns out my time in my home country prepared me well for the hardships in America.

Seven years into my stay in New York, I received my residency card, and yes, it was hard fought. But this state and this country will always be my second home because I also received acceptance as a journalist, two academic degrees, friends that have loved me like family, and that never-ending search for purpose, which had finally come to fruition. It was here that I realized I am a writer. I am a storyteller. I fight for those who may not have a voice. And I have been imbued with that Empire state of mind, a sense of “I am, I decide.”

I thought I had been accepted in New York as ‘one of us.’ But clearly, and to my surprise, that was not the complete picture.

As a television anchor and reporter, I was inside residents’ living rooms several nights a week, and highly visible. People recognized me, and would often come over to say hello or tell me what they thought of a particular story I had covered. As with others in the public eye, I had become somewhat of a curiosity in the best sense of the word. And most days it was simply part of the job.

Then there were the viewers who would let me know: “Your English is really good.”

Or: “I never thought an Indian chick would be attractive. Are you sure you’re not mixed?”

And finally, the comments made in discussion forums or calls to the newsroom from annoyed viewers: “Nigger, get out of town.”

It was alarming and yet strangely familiar. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. Here I was, decades later, with that same queasy feeling in my gut. But the difference this time around was my ability to really understand this type of behavior. Years ago I had learned that people are often afraid of what they don’t know. To an extent, this was the same thing.

My high school reunion happens to be this weekend, an event that brings mixed feelings for me. As the people I knew in school address each other on social media and make it seem like it was one big, happy family, I am reminded how many of these same people tortured the “lesser,” the “not so cool,” and the “racially different.” I watch these mean girls and boys make plans now, the same ones who had voiced their displeasure with me and had directed racial epithets at me. Some of these people have children of their own today. I wonder what they would think or do if their children experienced what they forced on me and onto so many others in school? Although I have healed in my own way, the questions and the enduring scars remain. While I would like to see how some have turned out, there are still others I have no wish to see. The truth is they likely have no idea of the damage they caused.

It’s easier to condescend than to understand. It’s easier to ignore than to discuss. It’s easier to define someone in a box than to hear his or her story. Many of those who made comments to me and about me had set their boundaries long ago. They had never been to another country, experienced another culture up close and personally, or tasted another cuisine. They were a product of their environment, unable or unwilling to allow other experiences to inform their own. I guess if they choose to repaint their school days past in hues of pink, they likely believe that reality won’t ever peek through that veneer.

If I could speak to that girl I had been, I would tell her that there is a big world out there for you. I would tell her please don’t be discouraged, don’t fret over the names, the humiliations, the threats. Don’t worry that your situation will not improve because it will. You will see there are so many people who are just waiting for you, and this time shall pass. Have faith in yourself, and love yourself, because loving yourself is the first step to a future.

Today, I hope I’m someone who is a blend of her experiences. I still seek to understand what motivates the discrimination that I’ve lived through and thus far, I can only conclude that some people have the need to find a scapegoat. They target those whom they perceive as weak and vulnerable, and in the process feel better about themselves. For my part, I have chosen to find my strength in words, experiences, and relationships. I have learned to speak five languages and have traveled to other countries and worked with those who help fight the good fight, be it for issues of human rights violations or inequality.

I have long ago forgiven those kids who hurt me in elementary and junior high school, or those who hurt me in my early adulthood, because you forgive – for yourself. Forgetting is another matter entirely. However, the scars have forced me to search out a new life, a much broader scope to value my fellow man, and open my heart to so much more. I don’t judge people on the basis of color, creed, gender, religion, or sexual preference. It’s part of being evolved towards becoming a full and complete human being, to overcome one’s own biases and prejudices, to live in a world full of variation and to appreciate those differences.

I know now that I had been given a gift as a young girl. Through the pain of hate and intolerance, I have derived a better sense of myself, of my family, and of my community. There is no anger anymore, perhaps just a little disappointment. I still believe we can bring about change through discussion. There is always another side to explore and understand.

And so, I give you another four-letter word. Hope. I guess I must be in the right profession. Hope is what we sell.